In the final season of the TV series Succession , media mogul Logan Roy pleads with his conniving, power-hungry children to back the sale of the family empire. He has no faith they can successfully operate the business in his absence. “I love you,” says the patriarch to his children, “but you are not serious people.”

Today, I reflect on this message with the heads of sustainability and ESG at energy firms, industrial companies and global banks in mind. Are they “not serious people”?

ESG leaders typically have no influence over their company’s future. Most lack credibility with the top execs, board members and investors. They have no budget or power to do anything that would actually address climate change. And they have almost no chance of ever becoming a CEO, CFO, COO or CTO in their companies.

Instead, ESG leaders usually come across as reputational décor. Well-educated, charismatic and overpaid, many seem to be tasked with proving, contrary to reality, that their companies are doing something serious about climate change. Meanwhile, they continue to pump, use or fund fossil fuels, a product “incompatible with human survival,” as UN Secretary-General António Guterres said last week. “Trading the future for 30 pieces of silver is immoral,” Guterres added, comparing the fossil fuel industry’s betrayal of humankind to that of Judas.

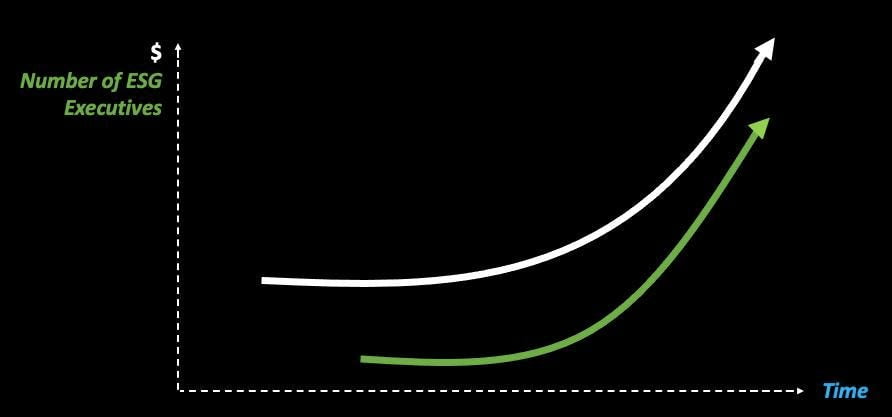

Does a strong correlation exist between the growth of Chief Sustainability and ESG Executives and … [+] the growth of oil & gas profits?

Wal van Lierop

If companies were serious about climate change and the need for net-zero emissions by 2050, surely they would put serious people in charge of executing the energy transition. Yet, for years now, I’ve seen energy companies, industrials and banks hire sustainability and ESG leaders who will never, ever touch the core of their business.

Last year, for example, JP Morgan Chase brought on a head of sustainability from a D.C. lobbying group known for pushing natural gas. “It is an incredible opportunity overseeing trillions of dollars in sustainable investments,” wrote this ESG leader in a post announcing the new role.

Seriously? Overseeing multi-trillion-dollar sustainable investments? Best I can tell, the job is to serve up green(washed) appetizers, braised in sustainability doublespeak, that distract from the main course: fossil fuels.

It is fossil fuels, after all, that still attract trillions from financial institutions. Banking on Climate Chaos, a report produced by a nonprofit coalition, identifies 60 global banks that lent or underwrote $5.5 trillion for fossil fuels between the Paris Agreement in 2016 and 2022. JP Morgan Chase topped the charts with $0.44 trillion for hydrocarbons, followed by Citi at $0.33 trillion and Wells Fargo at $0.32 trillion. In 2022, Royal Bank of Canada had the dubious distinction of financing $40.6 billion for fossil fuels—the most of any global bank that year.

ESG leaders in financial institutions regularly deflect accusations of hypocrisy by pointing to the lofty—and misleading—promises from their fossil fuel investees to decarbonize. Take Shell as an example. It promises to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. In 2022, Shell posted profits over $42 billion, the most in its 115-year history, thanks to high oil prices. Substantially all these profits are being returned to the shareholders in the form of excessive dividends and share buy-backs.

Moreover, an SEC complaint alleges that just 12% of Shell’s $2.4 billion of investments in “Renewable and Energy Solutions” actually goes to renewables. The rest funds natural gas projects. Said differently, Shell invests less than $300 million annually—just 1.5% of its total yearly investments and not even one percent of its 2022 profits—into renewables. They aren’t serious about climate change.

Meanwhile, Shell’s stock price has lagged peers that have even further ratcheted up oil production and dividends while freezing or cutting investments in clean energy. So, Shell’s new CEO, Wael Sawan, plans to maintain or slightly increase fossil fuels production this decade. And he’s already preparing to let clean energy investments fail. As the Wall Street Journal reports , Sawan “…doesn’t believe renewable- and low-carbon energy projects should be subsidized by Shell’s fossil-fuel profits, but should deliver returns that merit continued investment on their own.”

Seriously? Globally, fossil fuels benefited from a record $1 trillion of subsidies in 2022 according to the International Energy Agency. In other words, a quarter of the $4 trillion in profits generated by the industry in its best year ever came from taxpayers.

Is that “merit,” Mr. Sawan? Perhaps if the clean tech industry could spend $750 million annually on climate communications and lobbying—as BP, Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies collectively did in 2022—maybe it, too, could prove its “merit.”

This is why fossil fuel companies and banks don’t have (or keep) serious people in ESG. If someone took the job seriously—and against all odds, succeeded—these companies would have to forego short-term profits for the hard, courageous work of creating a clean future.

Luckily, a few bright exceptions are emerging. For example, one of the world’s largest pension funds, ABP of the Netherlands, recently sold all its holdings in fossil fuels, claiming it could not persuade the sector to decarbonize quickly enough.

Still, most financial institutions and energy companies intentionally and shamelessly hand climate change to people they don’t consider serious. These sustainability and ESG “champions” are, by and large, willing to equivocate, spin, lie and, most importantly, protect the status quo. That is why serious people increasingly research, launch, fund and join climate tech ventures that strive to make decarbonization an economic inevitability rather than a moral choice. They can’t do serious work in large corporations (or government).

Can anything be done? If banks became financially responsible for the carbon content of their investments, I think there would be a serious change in sustainability and ESG personnel. Lending billions to oil and gas companies would entail serious liabilities and costs. Serious investors, scientists and technologists would be hired immediately to mitigate risk and find cleaner business opportunities while governments (finally) cut the $1 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies.

Until then, a seven-figure paycheck is a cheap price for a Greenwasher-in-Chief to provide a reputational shield for a dying and destructive yet profitable business. The ESG people who refuse to sell their conscience have one decent option: leave. Encouragingly, I have seen a few examples of that. If you don’t take yourself seriously, who else will?

The energy transition is a serious thing. To succeed, we need serious people all around.