Skills Data

Guild

At one of the biggest annual gatherings of edtech entrepreneurs and investors this spring, I found myself in yet another brainstorming session about skills data where the outsized — and almost feverish — focus was on perfecting the data, rather than what to do with it.

We are already awash in skills data, the fruit of at least a decade of painstaking work. And with the advances in AI, our data quality is getting better every day. It’s not being effectively used to improve real people’s work and lives, though, because we all seem to be waiting for even better data.

We can’t afford to wait.

Our systems for opening up economic opportunity are ailing. And we’re all acting like research scientists, who build on years of study, rather than doctors, who triage and address what they can with what they know. We need to do both.

Improving how we define, measure, and document skills over time is important, but it’s not the end goal. The point is that we want to stop relying on proxies like degrees. We want to open up good jobs to more people, and help more companies fill the roles they desperately need. We want more people and more industries to grow and thrive.

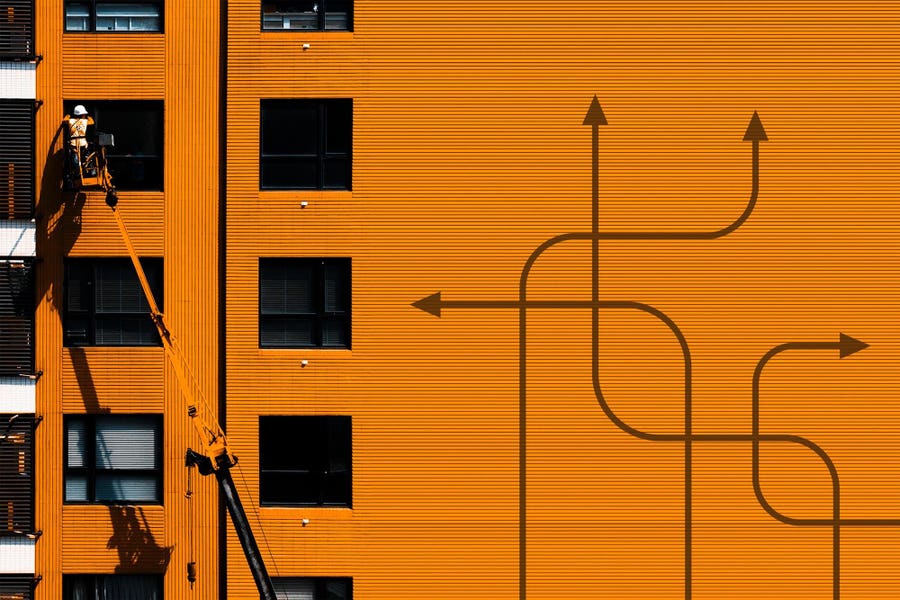

We’re putting outsized energy into perfecting skills data not because it’s the most important work, but because it feels like a problem we know how to solve. How do we make data accurately reflect what people know and can do? That’s a hard problem. But it’s not the wicked problem.

The wicked problem is: How do we actually use it to change people’s work and lives?

Answering that is an enormous and intimidating undertaking, but waiting for perfect skills data isn’t going to make it any easier. And time is wasting.

More than 10 million jobs are open today — and many of those unfilled roles are critical not only for economic stability and growth but for society’s safety, health, and sustainability. (Think cyber, nursing, and EV tech.) Moreover, there are 32 million Americans working in low- or middle-wage jobs who have the skills to move into higher-paying roles, but who are being held back by the lack of a degree.

The problem, in other words, requires triage: We need to use the skills data we have to unlock opportunity for them now, and operate on what we do know.

A subset of corporate innovators agree, including Maxwell Wessel, a former fellow at Harvard Business School who is now Chief Learning Officer at SAP.

He was at the recent discussion on skills data, and was vocal about the idea that we’re focusing too much on perfecting our data architecture and not enough on ways to actually use it to change the world of work.

“We spend countless hours talking about the thousands of skills we’re seeking to identify,” Wessel says. “In reality, most of our organizations are facing big changes that require us to be thoughtful around the 5-10 skills we really need to build at scale. Getting that thinking done and then getting into the real workforce change is so much more important than getting the skill definition perfect.”

Here’s just some of the real workforce changes that we should be focusing much more time, energy, and money on:

- Creating experiences to help people understand their career options and make informed decisions about their next steps. Understanding where people are trying to go —not just what jobs are they qualified for, but what kind of work they want to do. Their interests and aptitudes, not just skills.

- Thinking more about what sets people and jobs apart—such as by identifying the 5-7 skills that define a worker’s strengths or the core of a job, rather than simply cataloging all the skills that match.

- Developing better tools for capturing skills that aren’t captured by formal education or the typical job description.

- Creating more gateway roles that provide paths from the frontlines into career-sustaining jobs.

- Designing more ways for people to practice their next-level skills on the job, such as through modern-day apprenticeships or gig projects.

- Incentivizing hiring managers to actually focus on skills, rather than pedigree, when it comes to hiring.

Many of those things do require skills data — but it’s not sufficient. They also require a better understanding of people’s interests and goals. Of their identity as it relates to work, of their professional networks, and their ability to activate them. And they require a rethink of corporate structures and how department heads and frontline managers are rewarded when it comes to managing their teams.

They require leadership, culture change, and new ways of doing the business of hiring and promoting. Those are human challenges, not data ones.

Another human challenge: We like to see progress.

And that’s why it is so critical that we start seeing skills data put to use. More and more companies, and entire states, are on board with skills-based hiring—but if that momentum is to continue, they’re going to need to start seeing wins.

We’ve got to focus less on perfecting skills data and more on putting it to good use. Now. The window won’t stay open forever.