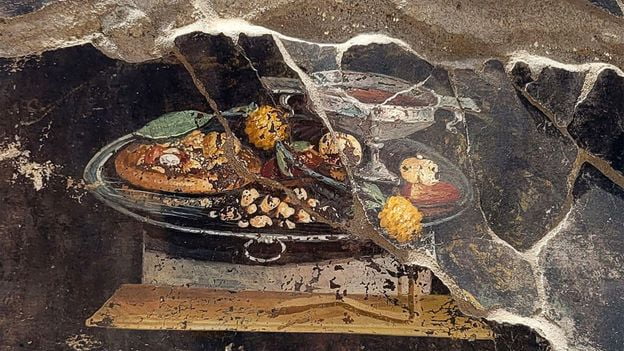

On 27 June, the Archaeological Park of Pompeii announced that a new fresco depicting a focaccia (an Italian flatbread) had been discovered . In recent years, the site has begun excavating previously unexplored areas of the once bustling town that was buried during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

In the announcement, director Gabriel Zuchtriegel described a beautifully preserved still-life fresco depicting a cup of wine next to a focaccia on a silver tray holding various fruits and what looks like moretum , a Roman herb-and-cheese spread.

As the media caught wind of the new find, one phrase quickly rose to the top of Google search rankings: “ancient Roman pizza”. But is there enough evidence to confirm that the flatbread pictured in the Pompeian fresco is an early form of the beloved Neapolitan food ? The short answer is “no”, although it’s understandable why some may initially assume, after glancing at the fresco (see image below), that these flatbreads are akin to pizza.

A recently discovered fresco of a flatbread at Pompeii (Credit: Abaca Press/Alamy)

In the Italian version of the announcement , Zuchtriegel recalls a passage of Virgil’s Aeneid, which details the placing of fruit and other foods on top of breads (sometimes referred to as “cakes” in Greek and Roman literature) that function as “tables” ( mensae , in Latin):

“Aeneas, handsome Iulus, and the foremost leaders,

settled their limbs under the branches of a tall tree,

and spread a meal: they set wheat cakes for a base

under the food (as Jupiter himself inspired them)

and added wild fruits to these tables of Ceres.

When the poor fare drove them to set their teeth

into the thin discs, the rest being eaten, and to break

the fateful circles of bread boldly with hands and jaws,

not sparing the quartered cakes, Iulus, jokingly,

said no more than: ‘Ha! Are we eating the tables too?'”

As a classical archaeologist who researches and recreates the breads and pastries of ancient Rome, I immediately knew that the image depicted in the unearthed fresco was a very important discovery. For one thing, it’s the first pictorial representation of food placed atop a circular flatbread in a Roman setting, corroborating literary references, such as the Aeneid, to this practice in ancient Roman dining.

The fresco also helps to identify a flatbread depicted in a previously known Pompeii fresco, the “bread distribution” fresco from the tablinum of the Casa del Panettiere (House of the Baker), and the two bread images in tandem provide critical information regarding how this type of bread was shaped by hand, and why it took the form it did.

Fresco from the tablinum of the Casa del Panettiere (left and top right) and newly discovered fresco (bottom right) (Credit: Farrell Monaco and Abaca Press/Alamy)

In the fresco from the House of the Baker, small, circular flatbreads sit atop the kiosk shelf, and a ring is impressed into the surface of the bread, creating a trough and a slightly raised rim. The trough was most likely used to keep wet foodstuffs from falling off the bread’s surface as people ate it. This trough may also be present underneath the food, inside of the rim of the flatbread depicted in the new fresco, suggesting that the two breads are likely the same type.

This unusual flatbread is also represented in another archaeological setting near Pompeii: Paestum, an ancient Greek city that was a part of the former Greek colonies once referred to as Magna Graecia . At the museum located at the site , terracotta renditions of this bread are displayed next to various foodstuffs that were consumed in the area during the 6th and 5th Centuries BCE.

With three archaeological representations of this flatbread, and one with fruit resting atop of it, it’s now easier to decipher what it might have been known as to 1st-Century Greeks and Romans.

The 2nd-Century grammarian, Athenaeus of Naucratis, wrote of a leavened Greek “cake” called nastos , a round, flat cake categorised as placoûs or placentae , the ancient Greek terms used to describe pastries made of flour, cheese, oil and honey. According to Athenaeus, these cakes were used as sacrificial offerings and he wrote that they were topped with a coulis , or fruit purée, called caryca . Italian speakers will immediately recognise the similarity of this word to the verb caricare : to fill, which is exactly what nastos was designed for: to be filled with purée.

Two terracotta flatbreads surrounded by terracotta grapes, carob, pressed ricotta and a pomegranate (Credit: Farrell Monaco)

To the ancient Romans, this coulis-topped cake was known by a different name, and it was categorised as a type of Libum , the Roman equivalent to the Greek placoûs. The name of the Roman version of nastos can be read in the same passage previously mentioned in Virgil’s Aeneid in its original Latin text: instituuntque dapes et adorea liba per herbam (they place cakes of meal on the grass). Aeneas and his men then load the wheaten cakes with wild fruit. To Romans, therefore, nastos was most likely known as adoreum (plural, adorea).

In the 1st Century AD, Roman author and philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote in Historia Naturalis that Romans once made offerings of adorea . According to Roman soldier and senator, Cato the Elder, the word was synonymous with “glory”. And the late 4th- and early 5th-Century grammarian, Servius, tells us that adorea cakes (ie flatbreads) are made of emmer (hulled) wheat, honey and oil and are suitable for offerings.

With this information, it’s fair to say that the fruit-topped flatbread depicted in the new fresco at Pompeii, and the ringed flatbreads depicted on the fresco from of the House of the Baker – along with the terracotta depictions at Paestum – are adorea, not pizza. Afterall, the flatbread in the new fresco is topped with and surrounded by fruit; not meat, mushrooms or vegetables.

Following the announcement of the fresco, many have attempted to discern what some of the foods and objects in the fresco are. Here are my interpretations, which are reflected in the recipe below:

On the flatbread: cheese or fruit paste; a bay leaf (with perhaps a small slice of cheese underneath); a small apricot, peach or apple; quail eggs; and slices of apricot or peach.

On the tray: two citrons, a peach, a fig, two dates and chestnuts.

On the slat below the tray: possibly a reed, used to cut or pierce the pieces of fruit. (Pliny the Elder references the use of reeds in cutting and piercing soft foods.)

Farrell Monaco’s suggested toppings for adorea (Credit: Farrell Monaco)

Adoreum: a recipe of a modern recreation of Pompeii’s flatbread

By Farrell Monaco

yields 6 flatbread

Ingredients

For the flatbread base:

1kg (6¼ cups) emmer flour (see Note)

20g (4 tsp) salt

500g (2 cups) water

35g (¼ cup) bread starter (see Note)

48g (¼ cup) olive oil

48g (¼ cup) honey

For the suggested toppings:

24 fresh figs

ricotta cheese, optional

6 apricots or small apples

12 dates

12 quail eggs

240g (¾ cup) honey

Additional flour for dusting

Method

Step 1

To make the base, place the flour and salt in a large mixing bowl. In a separate bowl, combine your water, starter, olive oil and honey. Don’t stir it or dissolve the starter.

Step 2

Create a cavity in the centre of the flour. Pour half of the liquid into the cavity and fold the flour into it. As the dough becomes shaggy, add the rest of the liquid until the dough begins to bind together. If you have chosen a whole or coarser flour variety and the dough doesn’t bind, add more water, 1 tbsp at a time until it does. If you have chosen to use white “refined” flour, be mindful that less of the allotted liquid will create a malleable dough. Cover the dough and let it rest for 2 hours.

Step 3

Remove the dough and knead it for 10 minutes, cover with a damp tea towel and rest again until it doubles in size. This can take anywhere from 2 to 6 hours, depending on your starter, the flour you use, and the heat and humidity in your kitchen.

Step 4

Once the dough has doubled in size, pull or cut 6 even portions from the dough. Form each portion of dough into a ball and place it on a clean surface or a flour-dusted tea towel. After all the balls of dough have been formed, cover them with a damp tea towel and let them rise for another 2 hours.

Step 5

Preheat your oven to 190C/Gas Mark 5/375F. It is now time to shape the flatbread shell. On a flour-dusted surface, take each ball and flatten it with the palm of your hand to compress it or roll it out gently until it is about 2cm/¾ inch high.

Step 6

With a small cup of water nearby, dip the tip of your finger, thumb or knuckle into water and create the trough: this is a well that will run around the perimeter of the round of dough. Your finger should slide and not pull the dough. Make it as wide as your finger and be sure to press firmly down to the base of the shell. Press the centre platform of the base down gently so it’s flat and level with the rim of the shell.

Step 7

Bake the flatbread shells for 20 to 25 minutes until golden on a pizza stone or parchment paper. Let cool.

Preparing the dough for adorea shells (Credit: Farrell Monaco)

Step 8

Once the shells have cooled, it’s time to prepare the toppings. You have a lot of freedom here!

For each flatbread: take 3 figs and mash them into a paste. Coat the centre platform of the shell with the paste. You may also want to add some ricotta into the fig paste or smooth a few small dollops over it.

Step 9

Cut up a few slices of soft fruit, such as apricot, dates or fig, and dress the top of the paste with the fruit slices. I suggest trying this with a reed-like implement, such as a split wooden skewer instead of a knife.

Step 10

Place 2 small quail eggs between the slices of fruit and garnish with a small apple or apricot.

Warm ⅛ cup of honey and drizzle it over the fruit allowing the trough of the flatbread-shell to fill halfway. Stop drizzling if the trough begins to overflow. Serve and enjoy!

Notes

It is unknown at what extraction rate the flour was processed to make the Pompeian Adoreum. Use a fine or bolted (bran content sieved out) product. If you cannot locate emmer flour, you may use spelt flour or fine whole or white common wheat flour.

If you do not have a starter, you can create a “sponge” by mixing equal parts flour and water with 1 tsp of commercial baker’s yeast. Stir and let it activate until it begins to rise. Use 35g (¼ cup) of this sponge as your starter.

Tasting and pairing notes

You may wish to pair this with some of the other items featured in the fresco such as red wine, chestnuts and citron. Another addition that isn’t indicated as a topping for nastos or adoreum, but would please the modern palette, would be some crumbled, aged cheese.

As you taste this Roman pastry, remember that it isn’t the same as a modern galette or Danish: it is a simple, rustic, Roman honey-cake topped with seasonal fruits. It is also an opportunity for all of us to explore the culinary practices of ancient Rome and the cultural heritage of Pompeii with our hands and our tastebuds. And what a wonderful experience it is to celebrate the recent discovery of this early form of pastry in this manner, even if we’re doing it from afar. It may not be pizza, but adoreum is quite literally a glory to behold, and a reminder that the breads and pastries we adore today have journeyed to our tables through millennia and from places that are often oceans away. And this time, from Pompeii.

( Farrell Monaco is a classical archaeologist, baker and writer. She is currently an honorary visiting fellow at The University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History. She is the 2019 winner of Best Special Interest Food Blog Award by Saveur Magazine and author of the forthcoming book: Panis: The Story of Bread in Ancient Rome.)

BBC.com’s World’s Table “smashes the kitchen ceiling” by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.