On the western edge of Fayetteville, New York, East Genesee Street cuts a straight, wide swath past 19th-Century brick mansions and the clipped greens of a country club. Downtown, the road narrows as it passes cafes and banks and crosses a burbling creek.

Today, this quiet suburb of Syracuse reveals little of the radicalism that roiled central New York state in the 1800s before spreading across much of the United States. Abolitionists, temperance advocates, prison reformers, progressive educators and – above all – women’s rights advocates all founded or nurtured important national movements in this area.

In fact, three women from central New York rose to the leadership of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which was founded in 1869 and aimed to secure women the right to vote. Two of those women are now household names in the US: Elizabeth Cady Stanton , who helped organise the US’ first women’s rights convention in 1848; and activist Susan B Anthony , who drew national attention when she was arrested for voting in 1872. But the third, Fayetteville’s Matilda Joslyn Gage , was almost lost to history – and that’s likely because she was the most radical of them all.

Gage has been called, “the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time” (Credit: Library of Congress/Getty Images)

Unlike her better-known colleagues, Gage didn’t only focus on women’s suffrage. She wanted to extend human rights to all Americans, including Black and Indigenous people. And unlike most of her fellow suffragists, she didn’t hesitate to attack the foundations of American society to further her cause. In her blistering 1893 book Woman, Church and State , she forcefully argued that organised Christianity had oppressed women for centuries. As a result, many suffragists ostracised her.

However, Gage would have the last laugh. When the book was reissued in 1972, it inspired a whole new generation of activists. In 1980, philosopher Mary Daly cited Gage as “a major radical feminist theoretician and historian whose written work is indispensable for an understanding of the women’s movement today”.

Daly wasn’t the only 20th-Century feminist inspired by Gage. “[Journalist and activist] Gloria Steinem says Matilda was the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time,” said Sally Roesch Wagner , founder and former executive director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation .

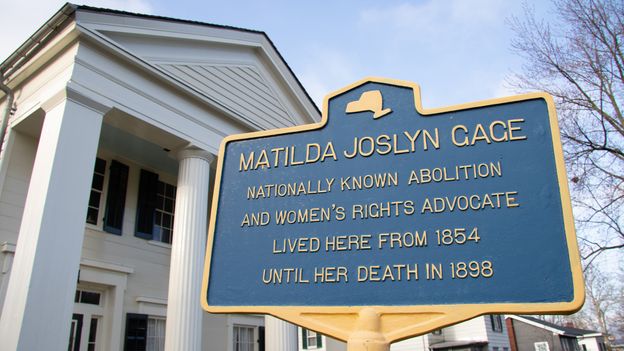

In the foundation’s museum, located in Gage’s former Fayetteville home, Wagner explained her decades-long fascination with Gage.

Gage (bottom row, second from right) felt other suffragists had destroyed the women’s rights movement by bringing conservatives into it (Credit: Library of Congress/Getty Images)

It began in 1973, when Wagner decided to visit Matilda Jewell Gage, a family friend and the granddaughter of the suffragist. As a graduate student, Wagner had little interest in 19th-Century women’s rights advocates, dismissing them as demure “teacup ladies”. All she wanted from the visit were a few familial anecdotes about the senior Matilda to liven up a women’s studies course she was teaching.

However, a heap of yellowing letters, scrapbooks and manuscripts on the dining room table intrigued Wagner. She spotted a letter the suffragist had written, claiming that Anthony had destroyed the women’s suffrage movement by bringing conservative women into it. The letter also called Stanton a “traitor” for joining Anthony’s newly expanded women’s rights organisation. These pointed attacks on America’s two most revered suffragists caught Wagner’s attention.

“That was it. I was hooked,” Wagner recalled.

After finishing her master’s degree in psychology, Wagner enrolled in a PhD programme that would lead to one of the US’ first doctorates in women’s studies. The topic of her thesis? Matilda Joslyn Gage. Wagner’s research eventually brought her to Fayetteville, where she and a team of volunteers raised $1m to buy Gage’s white-pillared home on East Genesee Street, renovate it and start the foundation.

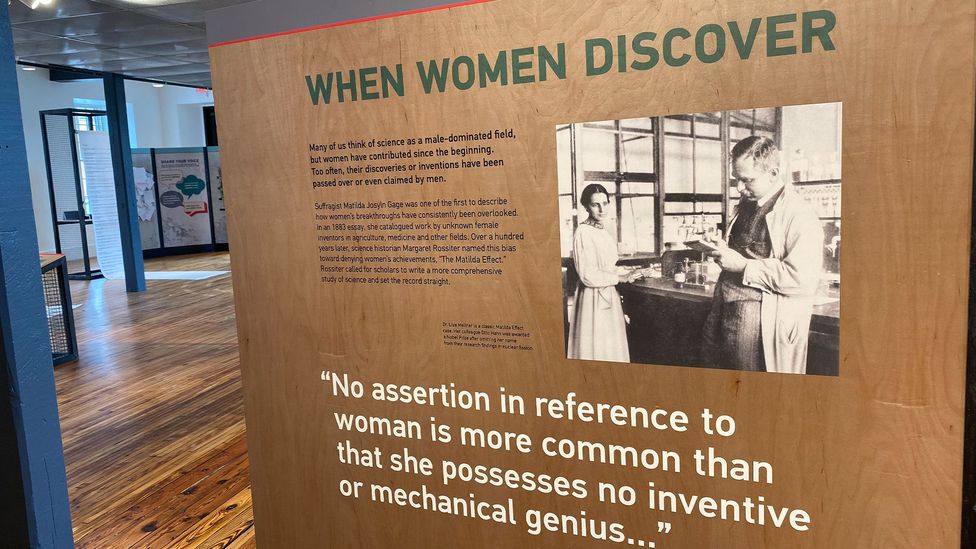

Gage inspired the term the “Matilda Effect”, which travellers can learn about at the National Women’s Hall of Fame (Credit: Laura Byrne Paquet)

From the beginning, Wagner knew that she wanted to create a museum that honoured Gage’s unconventional tactics and progressive ideas – and those tactics and ideas were legion. For instance, Gage’s 1870 pamphlet, Woman as Inventor , argued that women had invented the deep-sea telescope and numerous other innovations, but rarely received public acclaim for them. (In 1993, science historian Margaret Rossiter coined the term the Matilda Effect to describe the tendency to diminish, ignore or miscredit the work of female scientists.)

While helping to lead the NWSA in 1876, Gage and Stanton co-wrote a Women’s Declaration of Rights and Articles of Impeachment Against the Government of the United States. In it, they argued the government was violating the US Constitution in multiple ways, such as denying women the right to a jury of their peers (only men could serve as jurors) and subjecting women to taxation without representation.

Gage, Anthony and a small group of women stormed the podium at the American Centennial celebration to present the declaration to then-US vice president William A Wheeler. The stunt garnered attention for the cause and the declaration propelled arguments that would ultimately lead to women winning the vote in 1920.

In another act, Gage brandished a bullhorn on a cattle barge in New York Harbor to protest the 1886 dedication of the Statue of Liberty. Because women couldn’t vote in national elections, Gage and her fellow protestors saw the female symbol of freedom as “a gigantic lie, a travesty and a mockery”.

Travellers can learn about Gage at the National Women’s Hall of Fame, Women’s Rights National Historical Park and Gage Museum (Credit: Randy Duchaine/Alamy)

Much of Gage’s work within the NWSA took place behind the scenes: organising conventions, writing editorials, editing suffragist newspapers and circulating petitions. “Stanton and Susan B Anthony were more like the movie stars, who went out and lectured. Matilda stayed home and did the actual work,” said Angelica Shirley Carpenter, author of the book Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist . Carpenter noted that Gage also helped set up many local and regional NWSA groups, creating a solid national structure for the organisation.

Though she’s best known for her role in the women’s suffrage movement, Gage’s work was broad. In an era when many white settlers feared Indigenous people, Gage admired the Haudenosaunee , who lived in New York state. In their matriarchal society, when couples separated, women gained custody of their children and could retain all the property they had brought to the marriage – rights non-Indigenous women in the US didn’t have. “Never was justice more perfect; never was civilisation higher,” Gage wrote of the Nation. In the 1890s, the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk (a Haudenosaunee member Nation) honorarily adopted her and gave her the name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi (She Who Holds the Sky).

And in one of her more surprising contributions to posterity, Gage urged her son-in-law, L Frank Baum, to record the stories he told his children. He would go on to write The Wonderful World of Oz. Many Oz enthusiasts believe Gage’s feminist views strongly influenced that childhood classic, noting that both Dorothy and Princess Ozma (the ruler of Oz in later books in Baum’s 14-volume series) are strong female characters. “There is definitely a huge connection between Oz and Matilda,” said Allison Lehr, manager of the All Things Oz Museum in Chittenango, New York.

Gage died in 1898 at the age of 71 and didn’t live to see Oz’s publication.

Dorothy’s ruby-red slippers are displayed at the Gage Museum (Credit: Laura Byrne Paquet)

Today, visitors can learn about her at several New York sites, including the National Women’s Hall of Fame and Women’s Rights National Historical Park , both in Seneca Falls, New York. However, it is the Gage Museum that explores her ideas in the greatest detail.

To honour Gage’s life, individual rooms within the museum pay homage to her broad legacy. The Women’s Rights Room features a timeline of American feminist history. The Oz Family Parlor is decorated with Gage family photographs and Oz memorabilia. The Haudenosaunee Room displays artworks combining Tuscarora beadwork and non-Indigenous quilting.

When Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 requiring formerly enslaved people to be returned to their previous “owners”, even if they were in a free state, Gage signed a petition against it, and there is anecdotal evidence that her Fayetteville house was an stop on the Underground Railroad. Today, the names of many freedom-seekers who came through Syracuse are painted on the ceiling museum’s Underground Railroad Room.

The Gage Foundation also runs various programmes designed to foster discussion and critical thinking. Its Gage Ambassadors initiative offers field trips to Indigenous communities and other sites to help high school girls see the world from other perspectives. “Dialogues” bring together adults with differing opinions on topics ranging from abortion to reproductive rights of LGBTQ+ people to talk things through and, ideally, find some common ground.

Gage’s tombstone reads: “There is a word sweeter than mother, home or heaven. That word is liberty.” (Credit: Laura Byrne Paquet)

Even the museum’s design aims to encourage free expression. A sign at the entrance reads, “Check your Dogma at the Door. Keep Open to New Ideas. Think for Yourself.” Inside the house, walls are primed with whiteboard paint so visitors can record their reflections on them in marker.

At the end of my day at the museum, I mentioned that I was planning to visit Gage’s grave. Wagner insisted on driving me to the nearby cemetery, where we clambered out of her car to view the rough-hewn stone. As the spring rain pelted us, Wagner said she came here often in the Foundation’s early days, when the inscription on Gage’s tombstone served as inspiration.

Riffing on the phrase “Mother, Home and Heaven” , the title of a 19th-Century collection of pious poems and stories , Gage’s epitaph reads: “There is a word sweeter than mother, home or heaven. That word is liberty.”

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List” . A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.